Kicking the can down the road

- By Hagen Pfeiffer

- •

- 28 Feb, 2018

(Read the entry "Caveat lector" first)

Large-scale IT projects often result from the perceived need to replace a core IT application of an organization. Typical cases in point would be a core banking system (CBS) for example or a policy management application or a customer billing system. More often than not the existing (“old”) application was developed internally and deployed decades ago, built upon technologies that would never be considered today.

Justifications for the idea of replacing the old system come in many shapes and forms:

- "Functional enhancements

are too time-consuming and costly – the competition is out-racing us"

- "Maintenance is becoming

a nightmare as the original system engineers are retiring and the application

has not been, well, perfectly documented over the years…"

- "A key technology of the

old applications is running out of vendor support."

- "If we were subject to a

merger, clearly, our tech platform would be thrown out – together with our

respective team"

- "Packaged software is readily

available in the market, much more powerful and less expensive"

to name only a few. The arguments presented prima facie look intuitively reasonable, quite compelling even, but do they really amount to a call for action?

The difficulty starts with the holy grail of corporate investment decisions: The business case. While any modern IT-solution would most likely outperform the old application the problem is this: The old application is up and running while the new one is not – the old application is up and running while the new one is not (sometimes one needs to be reminded of the obvious!).

This is a classic case of path-dependent investment decisions. The old application has been deployed, adjusted and refined again and again towards the forever evolving priorities of the firm; over the years it has been fully ingrained into the muscle memory of the organisational process landscape. On top of this it has been depreciated "many times over" (if such a thing were possible). The modern replacement candidate by contrast needs to be acquired/leased, configured, tested, deployed, adjusted and refined, and migrated to.

The transition program, taking several years to complete, is not only very risky ("open-heart surgery") and expensive per se but will en passant crowd out many other potentially lucrative investments of the firm in the meantime. And when the new system finally goes live, after all the blood, sweat and tears, the users will initially have a new tool that is - from a functional point of view – in some aspects inferior to the old system. Adding insult to injury, the overall amount invested into the project dwarfs the subsequent IT-cost savings after go-live by orders of magnitude. Regardless of how "creative" the project advocates are willing to be ("increased revenues" and the like), no discounted cash flow analysis is likely to ever come out with a positive NPV.

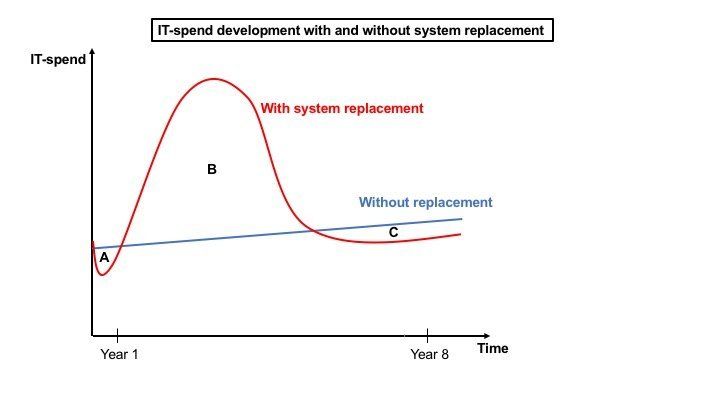

The chart above shows why: In the as-is scenario (blue line) the IT spend empirically increases by a few percent each year on average. In the replacement scenario (red line) the journey, counterintuively, often starts with a substantial decrease in year 1, the reason being that some development work on the old application is rightfully cancelled for lack of any future pay-off. But this is short-term only and quickly the firm experiences the anticipated huge increase in IT spend as a consequence of the migration project. After successful go-live of the new application IT spending will decline rapidly towards a new level, in the best case slightly lower than in the as-is scenario. In the worst case, IT spend will be actually higher due to the enormous backlog of business projects that was built up when the migration project displaced just about any other discretionary IT investment. Now, look at the chart again and compare area A+C with area B; then do it again while applying an annual discount factor!

In conclusion: Except for rather special circumstances (e.g. merger, fundamental change of business strategy) there is no financial business case to be made in favor of such a project. And if there appears to be one, you should be very doubtful. So, for once, corporate executives, with their responsibility for increasing the value of the firm (over the course of their contract period), should not be criticized for procrastination, for kicking the can down the road, for leaving this peculiar corporate problem to their successors or someone else to solve. Fortunately, however, there is a "someone else": The owners of the organization or their representatives.